The Art and Life of Dee Ridley: Part One – Double Face

Jo Manby

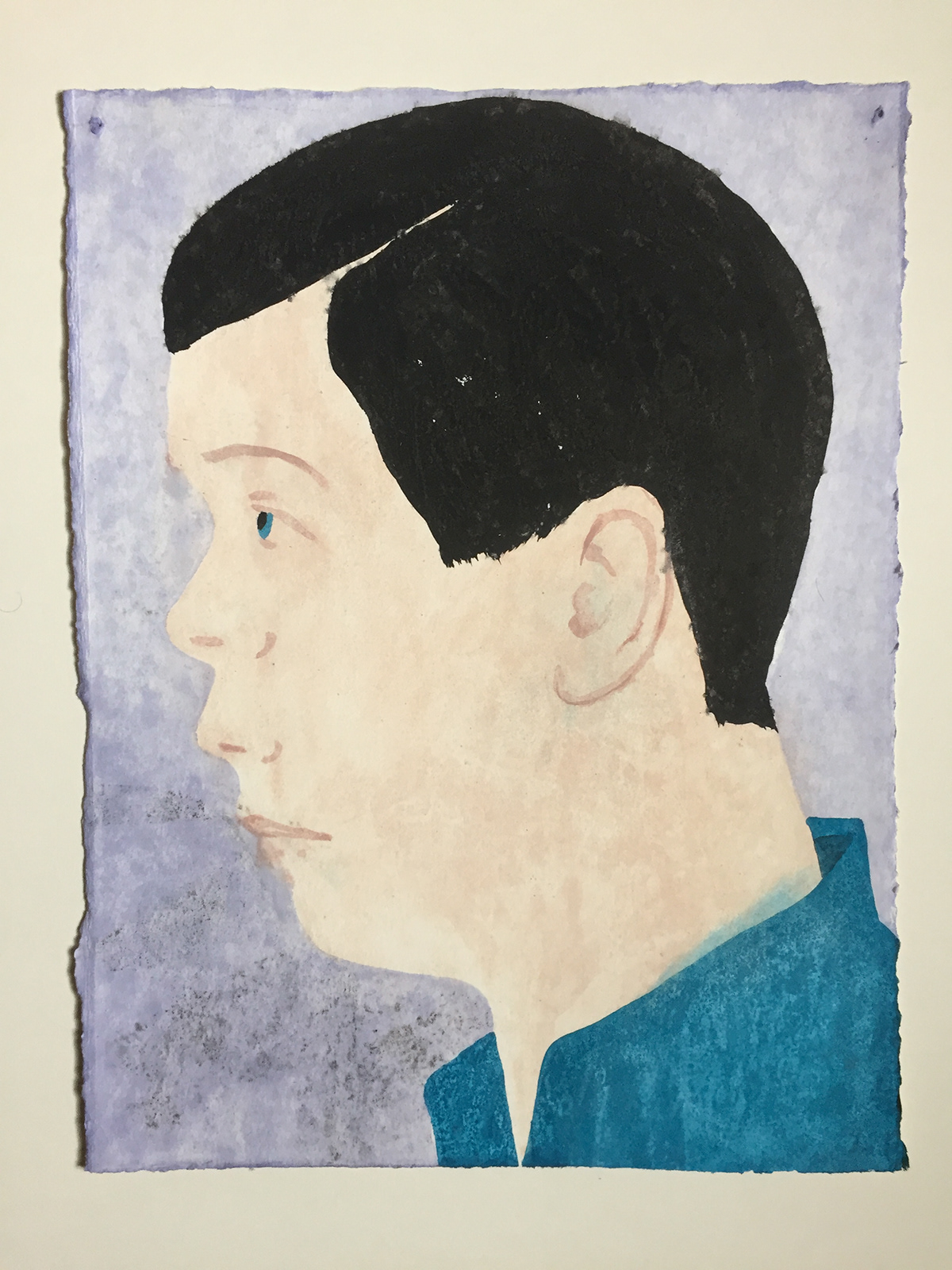

James Rielly, – Some have no home, 2018

‘Double Face’ marks the first part of a series of creative texts by writer Jo Manby. Follow her character Dee Ridley on a visit to ‘Into A Light’ at Saatchi Gallery in London and ‘Native: Manchester’ at PAPER in Manchester. Read ‘Part Two – Nettle Sting’ here and ‘Part Three – Fenced Up’ here.

I’m with Perry’s daughter, Camille. We’re about to leave her London apartment. She wants me to check out some oil paintings. Early 20th century British. Nothing wrong with that, in principle. Camille gets me to give her the nod if I think something is of worth. But to me, it’s all getting a bit jaded. The gilding rubbing down to the wood. I’m just in it for the cash these days.

Perry’s a strange one. Difficult to say what he does exactly. He gave Camille the best education – French finishing school, that kind of scene. Funds her art collection. The way he tries to get me involved with his dodgy dealings is one of the reasons why I’ve started to think I’d be better off heading back up north someday soon.

Anyway, for now, it’s business as usual. Though it’s early to be drinking, Camille comes through the door with a couple of glasses and a bottle. She loosens the cork and lets it pop. Bubbles sparkle. She hands me a glass. I start thinking about the first time I was here.

Must have been five years ago. I pretended I didn’t know much about it then; the collecting game, the paintings lined up on her white walls. And in a way, I didn’t. They screamed money at me though. I stood there squinting at one that was gilt-framed and half-unpacked; a bloke with half his face missing, tied to a swivel chair standing in a puddle of pink gore.

- Into Bacon? She’d said, noticing. Expensive tastes then, Ridley?

- I wouldn’t really know.

- No, I suppose not.

She sipped her champagne. (There’s always champagne at Camille’s.)

- But these are all acquired tastes, she said. It’s what you learn as you proceed through life.

I remember thinking: is that what I am? An acquired taste? Am I the kind of low life that’s somehow cool to have around when you’re rich like this? Your wealth might look good from here – an apartment in the West End – but not so good from the head of its source. A poisoned fountain ends up killing all the plants in the garden.

+

Since then, I’ve worked for Camille off and on. I was dazzled to begin with, admittedly, and I still can’t complain about the money she sends my way. But the glamour is beginning to wear thin. I’m bored by the same uniform trends that seem to dominate the art scene around here. Where are the artists with something new to shout about?

- Let’s go, she says.

I drain my glass. The car arrives and the driver comes around to open Camille’s door. The smell of wealth hangs in the street for a minute, before floating away on the breeze.

- Let’s see if we can’t get you talent spotting, she says.

A wave of nausea passes through me.

+

Halfway down King’s Road, I ask the driver to stop. I’m bailing out, I tell Camille.

Relief as I feel the pavement beneath my feet. Local Chelsea school kids play football on the grass. Doppler effect as a plane overhead tears up the blank page of an occluded sky. One of the few benefits of living in the capital is that nobody knows who you are or where you’ve come from – despite the fact that I’ve remained here much longer than originally planned.

I head towards the Saatchi. My friend Richard mentioned an exhibition in passing the other night which caught my attention. A group show; names I’m unfamiliar with.

+

Crossing the green and entering the Duke of York’s HQ, I head upstairs (more out of habit than choice) to give the main shows a cursory glance before descending to the Prints and Originals Gallery. ‘Into A Light’, the exhibition is called. I’m unsure of what to expect.

I find it filled with what appear like small windows onto worlds rooted in experience rather than reality. I get the impression of many voices discussing, imagining. The mood is vibrant, still, alive, considered.

Outside, day frays to dusk and the traffic turns on its red and white lights. Outfits shimmer off fashion shoots to parade for the oncoming night as I study nightclubbers breathed into life out of oil shoved around zinc sheeting in a series of paintings by Casper White. I suddenly feel the old, familiar sense of excitement and pull out my phone to type White’s name into Google. He was awarded the BP Portrait Travel Award in 2017 to paint the clubbing subcultures of Berlin and Majorca. Makes sense. There’s something refreshingly present and alive about the way he’s captured each scene. Movement, sweat, music, makeup and energy pulsate out of the thick layers of paint cut through with gel colour lighting, glistening in the heat. He was clearly there; in it. Reminds me of my wilder days back in the 1990s.

Casper White – Daniel, 2018. Image courtesy of LLE Gallery

A set of tiny drawings delicately rendered in Chinese ink capture me next. They all seem to focus on hands, which – I later gather from an interview with the artist, Lisa Wilkens – is because they’re based on images from a 1940s first aid book about how to hold the hands of people who have been injured. The concept sounded bizarre at first but then she went on to explain that the book related to a wider ideology that was emerging in Britain at the time: a belief that if the state looked after its people, the people would look after each other and themselves.

Lisa Wilkens – Unite #5, 2016

Now look at us, with our healthcare cuts and ever-decreasing social provision. Problems that exist only as abstract ideas for the likes of Camille and her dad. I think back to the first time I shook Perry’s hand and experienced a tremor of unease, sensing a gentle coercion in his attitude.

Nearby, a surreal conflation of imagery drawn from architecture, computer graphics, comics and sci-fi bursts out in an explosion of photorealism across a group of works by an artist called James Moore. I spend a while admiring how he seamlessly cuts and pastes different realities together; the historic, the virtual, the supernatural and the commodified. Scott Abandons Cardiff 1910AD, featuring a ship pranged onto an iceberg in a harbour, feels like 20th century surrealism reborn. Lonely beaches and bleached out skies, worryingly placid water, smooth paint and ironically temperate colours.

James Moore – Scott Abandons Cardiff 1910AD, 2018

I have another look at the introductory text panel by the entrance to the room. The show is a collaboration between two galleries I’ve not heard of before; LLE in Cardiff and PAPER in Manchester – my old haunt. Can’t have been around when I was last there. But then again, we’re going back a few years now.

+

On the phone to Camille the next day, I drop the exhibition into conversation. Trying to rouse her attention, I begin by contextualising some of the work for her – asserting a sense of weight and legitimacy by talking about how White and Moore must have studied Sickert, Gertler, Hitchens and Lucian Freud to paint the way they do. She’s audibly nonplussed, so I change tactics to what I know is mostly likely to appeal: a mention of the commercial sense in investing in ‘emerging’ artists from the regions, interest in whom is slowly on the rise. But she is firmly stuck on the capitalist merry-go-round of places like Bonhams and Christie’s, and begins to talk of other things.

+

A week later and I’m at my old schoolfriend Will’s house in Whalley Range – a leafy suburb of Manchester which I didn’t visit much growing up. It feels good to be back. He listens patiently as I go through the pros and cons of relocating here – a list that has started to develop and occupy my thoughts over the last few months.

I came up on a whim after noticing that PAPER had an opening I could make; a show called ‘Native: Manchester’ – fitting given where my head’s been at lately. Will didn’t fancy it, so I decide to go along on my own. The place is hard to find, tucked away on a back street near Victoria train station and through a gated yard. I pass through the small doorway and into a tiny room; softly lit and warm, full of people chatting. The handout says that the artists were each asked to make work in response to the question: ‘Where are you from?’ Perhaps the kind of exhibition we need more of at the moment.

I think back to my old man who grew up during the war. “We think we’ve beaten the Nazis but they’re like bad seeds – give them the right growing conditions and they’ll sprout back up again like horrible poisonous flowers,” he often used to say. If anyone ever asked him where he was from, he’d proudly inform them that he was a citizen of the world (even though he’d never been beyond Europe). I wonder what he’d think of the way things are shaping out today. Leaving Europe feels like quitting membership of the best club out there. No wonder everyone’s after dual citizenship.

I refocus my gaze across the four walls. The profile of a boy with a miraculous double face catches my eye first, though he somehow doesn’t feel out of place. Some have no home, the piece is called, by James Rielly. He reminds me of the lads I passed on my way over here whilst walking through Shudehill – the real-life counterparts behind the news headlines about rising levels of homelessness, depression and drug addiction. The dispossessed, the forlorn.

A couple next to me are discussing the artist, who, I learn, was born in Wales but now lives in Paris where he’s professor at the Beaux-Arts.

- He’s got all these visual tricks, the man says. But essentially his stabs-in-the-dark at child psychology are all about heartache and social inequity.

Pretentious, though what he’s saying seems to make sense. The subject of social inequality takes me back to Wilkens’ drawings at Saatchi, which I also read were shaped by her experience of growing up in a 1970s West Berlin household with Marxist-Leninist parents. As if affirming the connection, I notice that hands feature in Rielly’s work too as I move on to his piece no home for some in which a single disembodied hand holds the stem of a plant in front of two human eyes. No body, no corpus, no corporeality. Something similar occurs in a third work by the artist, which shows a faceless boy wearing a paper crown with two punched-in eyeholes. I suddenly feel compelled to tuck my own hands away in my back pockets, as if trying to hide them.

Crossing the room, I walk over to look at David Leapman’s tangled drawings in gold and silver ink. Each sheet of paper is covered in marks – massing, teeming, coalescing together. I can feel the pure energy fizzing from the page.

David Leapman – 10.4.16, 2016

I’m standing there trying to work out if the little colour constructions could be symbols on a map, when I notice the scent of cinnamon and coffee and turn around. A smiling girl with wavy hair. She says she doesn’t recognise me and asks if I’ve visited the gallery before.

A few beats into the conversation, she ventures:

- Doesn’t it make you feel like exploding, all this politics?

- I don’t really talk politics, I’m here for the art.

- What do you like best out of what you’ve seen?

Not ready for the question, I stall.

- Difficult to say. I can’t take any one work out of context.

- How do you mean? she says, looking up at me through her fringe.

- Once you have a context –

- An exhibition, she says.

- Well yes. In this case, an exhibition. It’s not easily subdivided.

She makes the kind of face that says you’re odd, but I like you.

- An interesting proposition, she concludes. Smiles again. After a pause, I turn back to the show.

I’m confronted by a print titled Hole Earth Catalogue by Chihiro Minato where flashes of other worlds appear through the cracked pavements of a busy street, and I’m back on King’s Road for a moment: walking with my head down, wondering what other possibilities might open up for me away from Perry’s sordid lines of business. I look up other works by Minato when I get home and, like Moore, he seems to make a habit of tearing up reality; as if ripping it from the pages of a magazine. From the gallery handout, I read that he’s a socio-anthropologist as well as an artist, and I find myself falling in love with the strange transnational realms he creates out of collided geography, architecture and demographics.

Before I leave, the wavy hair girl comes and tells me her name is Tamsin. Outside on the street, the rain falls.

Heading back to Will’s, my thoughts remain within the small gallery space. How is it that just as transnationalism and the prospect of a borderless world were beginning to seem like a valid possibility, global politics switched overnight and a universal move towards separatism set in. Running alongside these reflections, however, I’m surprised to find another, less familiar train of thought. The voices I have encountered over the past few weeks hold a fresh, rare sense of optimism. Boarding the bus, I find my own world beginning to shift slightly.

‘Into A Light’ is an exhibition of new paintings, drawings, and collages by eight artists selected by PAPER (Manchester) and LLE (Cardiff), presented at Saatchi Gallery (London). ‘Native: Manchester’ is an internationally touring exhibition featuring work by 20 artists selected by PAPER, Durden & Ray, Gallery Lara Tokyo and Art Office Ozasa.

Find the next instalment of The Art and Life of Dee Ridley here.