Behind The Times with Sarah Hardacre

Greg Thorpe

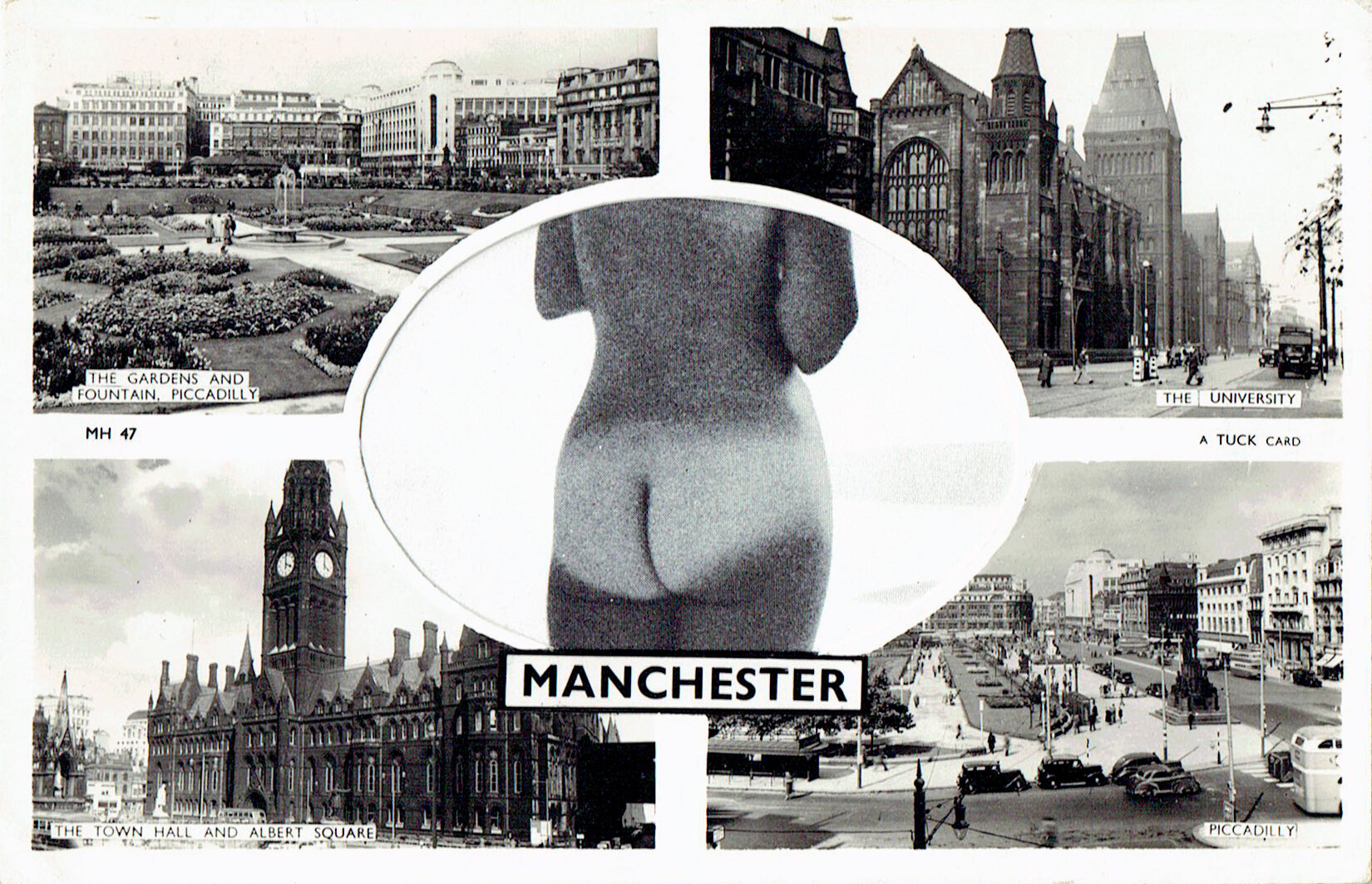

Untitled - Manchester 01, 2021, Vintage postcard and magazine cutting, 9x14cm

Greg Thorpe introduces ‘Behind The Times’, an exhibition at PAPER Gallery in Manchester (22 May – 26 June) featuring a body of new collage work by artist Sarah Hardacre, curated by himself. The show is the result of an 18-month-long collaboration between Sarah and Greg, initiated by PAPER as a development of the Fourdrinier project, and funded by Arts Council England. Read ‘Brutal / Beautiful’, an earlier in-conversation piece between Greg and Sarah, here.

Wish you were here

Mirabel Street is a modest comma of a thoroughfare that deftly shortcuts the Manchester–Salford border. It’s the only ‘Mirabel Street’ in Britain and counts amongst its neighbours the ancient Chetham’s School of Music, the gigantic Manchester Arena, the grand Victoria Railway Station, and the muddy old River Irwell, churning away beyond the bridges and walls. Halfway along the street is Mirabel Studios, an artist enclave with accompanying project space, PS Mirabel, and the two compact rooms of PAPER Gallery. Sarah Hardacre is herself a former Mirabel artist and visitors to PAPER are in fact standing in Sarah’s former studio. From 22 May to 26 June 2021, PAPER is/was/will be home to her new show ‘Behind The Times’. The scene setting is important, I think, because a sense of place is key to Sarah’s work – geographically, architecturally and temporally. I like to imagine the journey of the viewer as they approach the gallery, past ornamental bridges, grubby arches and city pedestrians, before coming to a stop across from the facades of the old Manchester Parcel Post Office. There is excellent brickwork everywhere you glance along the way.

At the top of my sprawling freelancer’s task list is this urgent plea: “Process rather than production!” Sarah’s new work in ‘Behind The Times’ is the culmination of a long process of collaboration between myself as writer/curator and Sarah as artist, initiated by PAPER as a development of the Fourdrinier project, and funded by Arts Council England. Our original creative team also included the artist Sadé Mica whose imagination and conversations directly helped initiate the ideas in ‘Behind The Times’. The project is inescapably embedded in our experiences of the COVID-19 pandemic, with all its fractured timelines, mental ill health, isolation, delays and disappointments. But from these tribulations emerged a strong sense that for us, thankfully, our work is not life or death, and a sense of creative playfulness can offer an antidote to our gruesome times. I also learned that the exhortation to ‘be experimental’ doesn’t have to mean grasping for something wild and unknown beyond our practice; it can mean looking deeply at what’s already in front of us and rethinking what we might concoct using good ingredients we already possess.

Postcards

At some point in the creative process – amidst successive lockdowns, project extensions and venue closures – we had to assume that we would not have access to a physical space to show new work. This would of course directly affect what the artists wanted to make. We began to consider how we might rethink both the opportunities and limits of a physical setting. Digital/online fatigue was a gruelling daily reality and not a format we relished since it dominated every aspect of our lives. Fairly soon we happened on the possibilities of the humble postcard as a way to circulate words and imagery from person to person at a time when we were forced to be apart. ‘Wish you were here!’ took on a different meaning as we Zoomed from our living rooms, offering something a touch more yearning than the insincere vacationer’s sentiment. Perhaps the show itself could comprise the making, printing, writing and receiving of postcards? A show always in transit. In retrospect, mail art and other artefact-driven projects such as zine-making did enjoy an upswing in the pandemic as we collectively thirsted for things tactile and unpixellated. In our artist/curator conversations we imagined postcards of lesser-known places such as Sadé’s stomping grounds of Moston and Malham where they often set their films. We thought of the types of imagery and kinds of bodies that postcards traditionally celebrate or omit. We came to understand and enjoy the postcard as an artefact that already bound us together. Sarah grew up in Holmfirth, West Yorkshire, a regular visitor to the Holmfirth Postcard Museum, former home of Bamforth & Co, creators of the nation’s saucy seaside postcards. And I grew up in Blackpool, arguably their spiritual home.

The new collages in ‘Behind The Times’ investigate and celebrate these rich histories of the British postcard and in doing so fulfil one of the key hopes and aims for this project – a meaningful development of Sarah’s work. The new pieces continue “the artist’s practice of contrasting sexual and architectural hopes and dreams,” as I previously characterised it. This means the unique trademarks of her work are in place – the vintage naked female body, the North, and the types of architectural structure whose utopian ideals and meanings shift irrevocably over time. The placement of these elements in the format of a postcard binds them together in new ways. Look carefully at the scenes selected by the postcard maker, and now the artist, as the basis of the collages. They offer triumphant celebrations of transportation, civic beauty, bureaucracy and progress across the North. Witness a pride in education, road building, tourism, city plazas, and all the concrete and commerce of Britain’s bright future. These provincial town and city scenes generate acute nostalgic sensations because they represent ideals of what we once thought of ourselves. In a sense they are the dreams of what we might have been. They are also humorous to an ironic contemporary eye, celebrating motorways, hotels and shopping centres – even the giro offices at Bootle – in the way other postcards depict the majesty of Roman fountains and Venetian canals. A quotation the artist often returns to is by Erich von Däniken, who writes, “Not until we have taken a look into the future shall we be strong and bold enough to investigate our past honestly and impartially." This is our vantage as contemporary viewers – we live in the future dreams of our ancestors. Sarah’s work invites us to be kind as we review these past Northern utopias – which might now be the neo-liberal ruins around us – and to be open to the hidden realities of our complex human natures, be that desire, sexism or corruption.

What of the nakedness? What of the glorious bums, bottoms and bare arses that grace and complicate these once-modern, now somehow ghostly hyper-colour urban scenes? Sarah’s work has repeatedly brought flesh and concrete together, troubling assumed binaries of male/female, public/domestic, and placing messy human desire via soft porn aesthetics alongside ideals of living. Phallic utopian buildings might be draped with soft female flesh and come-hither expressions. Sex itself disrupts nostalgia. The absurd pseudo-sexual scenarios of the naughty seaside postcard, for example, have always obscured the furtive and unspeakable nature of British sexuality, muting conversations we still struggle to have about desire, consent, agency, bodies, queerness, erotics etc. In their various ‘Carry On’-esque scenarios, traditional naughty postcards paired statuesque women with feeble men, or busty birds with dirty old geezers. Think Hattie Jacques dwarfing a shrinking Charles Hawtrey, or Babs Windsor keeping Sid James at bay, if only for so long. Sarah’s postcard figures offer something different, though are inescapably referential. Her women are often faceless but not exploited forms, their behinds sometimes androgynous, their bodies naked but not necessarily salacious or even sexualised enough to cause shame or discomfort as they land on your welcome mat. At least we think so. We hope so. The era of Sarah’s nudes seems to equate roughly with the period of the urban scenes, so they refute the innocuous innocence of those timelines. Pornography, sexism and lust must also take their rightful place in our heritage alongside public transport, libraries, shopping centres and homes in the sky.

Untitled - Blackpool, 2021, vintage postcard and magazine cutting, 9x14cm

Place and placement

As we pieced together the show, Sarah’s small untitled postcard works required an arrangement that would contrast with the natural geometry of the nine larger collages. Thinking once again about geography in her work, my suggestion was that we roughly attempt to map the relative locations of the featured towns and cities by their placement on the gallery wall. As we excitedly assembled what this might look like (“Hang on, is Sheffield further north than Liverpool?”), Sarah began to describe how the locations each held personal meaning for her – her youth spent in Huddersfield, her dad employed in Sheffield, childhood holidays to the coastal towns of Blackpool and Scarborough, copious trips up the M62 to visit family in Bury or Rawtenstall, jobs in Leeds and Lancashire, friends in Newcastle and Liverpool, and homes and studios in Manchester and Salford, including right here in Mirabel Street, in this very room. We suddenly understood this assemblage to be a topography of Sarah’s life and times, sharing places close to her heart and memory, as well as subjects that are instantly understood to be Northern – class, family, socialism – and those that aren’t but ought to be – hedonism, feminism, art. The special artist/curator synthesis in the assembly of this space was something really special as a result.

The second smaller room at PAPER is home to multiple reproductions of one of Sarah’s new postcard collages, offering vintage black and white scenes of Manchester city centre, neatly labelled in sans serif, with a serene naked white bottom taking centre stage in the panelled layout. This room is a place in flux – think of it as the post office sorting room, you might even call it a reference to the Sorting Office across the road. The postcards are shelved, piled up, displayed, written or blank, yours for the meddling. They can be taken away and posted to loved ones, inscribed and left behind, added to or moved around the space. Visitors will decide. Staying true to our original idea for the show to be a thing in transit, this space offers the postcard in its truest form, as a missive in motion, a reproduction of an original, something partly designed and partly un-curated, an item that can easily traverse the boundaries of PAPER. They are littered across the city, in bookshops, galleries, letterboxes and studios. We missed you. The weather’s awful. Wish you were here…

‘SMASHING’

The naked or semi-clad women who populate Sarah’s collage works often appear as pleased giantesses, cinematic ‘fifty-foot women’ who seem to own their surrounds, undaunted and undominated by their architectural setting. The male gaze that might once have pinned them to the pages of a porno mag now belongs to you, to us, to me. What do we see? Outside PAPER, the artist has commandeered the all-too-tempting expanse of brick wall on the adjacent apartment building to experiment with placing her women in a real bricks-and-mortar setting. Just as the postcard now seems a natural evolution for Sarah’s themes, so too does this real-life paper/brick collage open the possibility of exciting new evolutions for her work. Sourced from a vintage Morecambe postcard, the woman on the wall is transformed from hand-held to larger-than-life. Standing around three metres tall she is flush to the edge of the wall as she was once flush to the edge of the postcard, thus acknowledging the material reality of the building and drawing attention at once to her own structure and scale. For those isolating or distancing, she can be seen from the street, smiling and beckoning, and honouring the porous boundaries of the show as we originally imagined them.

Sarah Hardacre outside PAPER Gallery